I couldn’t have picked a worse year to publish a prediction model for German politics. There’s a global pandemic that continues to produce economic and social contexts that are without historic precedent (and precedent is important in predictions) and it’s the first election in 16 years in which Angela Merkel is not running for chancellor.

These two factors are turning the 2021 election into the most unpredictable election Germany has potentially ever seen… yet the results are going to be very similar to the last election in 2017 (according to the Vorcast Model). Read on for an overview of the current state of the race and the most likely coalition government scenarios Germany could end up with once all the votes have been counted on September 26, 2021.

Here are the main takeaways:

- The Green Party will almost certainly be part of the next government

- The Greens are not as strong as they currently seem in media discourse and polls

- Margins as small as 3% will decide which parties will form the next government

I’m going to run through the three most likely scenarios (and two highly unlikely ones). All of these scenarios are based on the Vorcast Model’s latest predictions at the time of posting (March 25, 2021). You can see the predictions for each party and how they deviate from the polls in the chart below. For more information on how the Vorcast Model works, head here.

Scenario I: 2017 redux

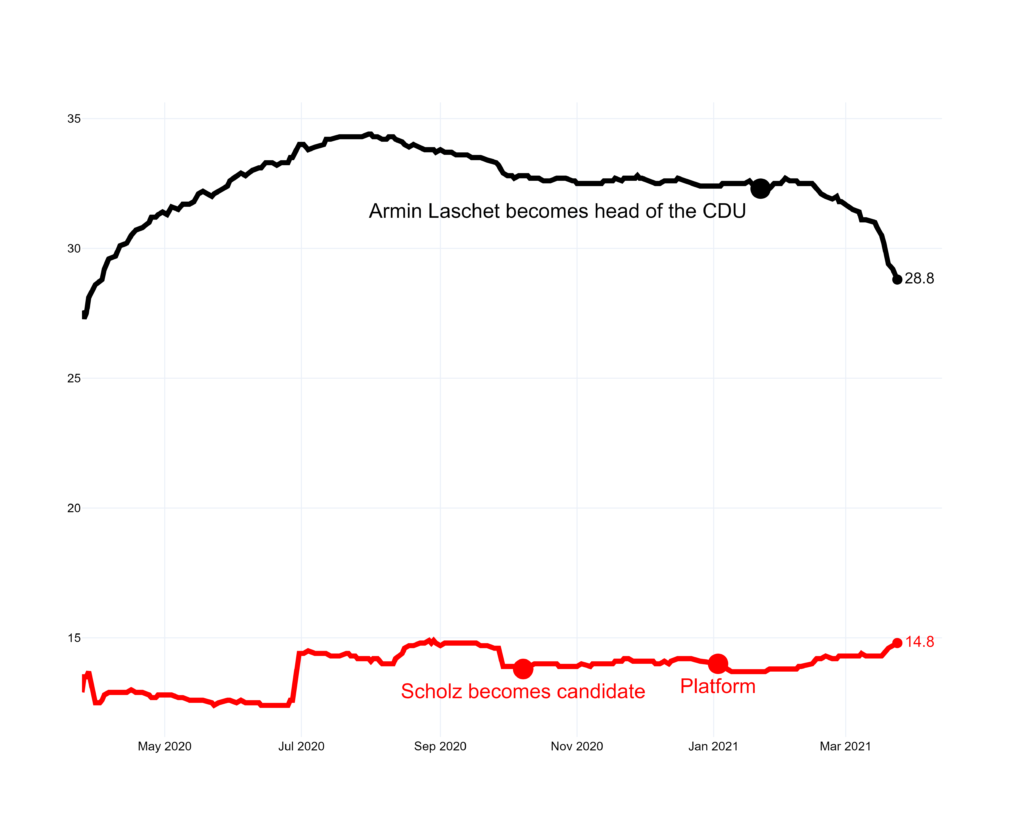

This scenario puts my money where my predictions are. It goes off of the Vorcast Model’s current predictions. As you can see in the interactive chart above, the CDU/CSU currently stands at 28.8%, whereas the Grüne are projected to win 18% — which would give them a combined vote share of 46.8%. This is extremely close to being a majority, but it will require the help of another party. This party will almost certainly be the FDP, which is currently projected to end up with 9.2%.

This scenario would be very similar to the result of the 2017 election. This time around, the Greens and the liberals (liberal being used here in the European, not the American, sense) roles’ will be reversed and the CDU/CSU will be less dominant. This would result in very complex coalition negotiations with Armin Laschet, the new head of the CDU/CSU — potentially trying to make up for a lackluster showing, a disappointed Grüne who underperformed their polls, and an FDP that has not fully reckoned with their dramatic exit from the same negotiations four years ago.

This is currently the most likely outcome of the 2021 election.

Scenario II: The Greens and the CDU/CSU join forces

As I mentioned above, the Grüne and the CDU/CSU currently have a 46.8% vote share according to the model. This isn’t far from a majority, meaning that with just 3 (comfortably 4 or 5) points more, they could form the new German government.

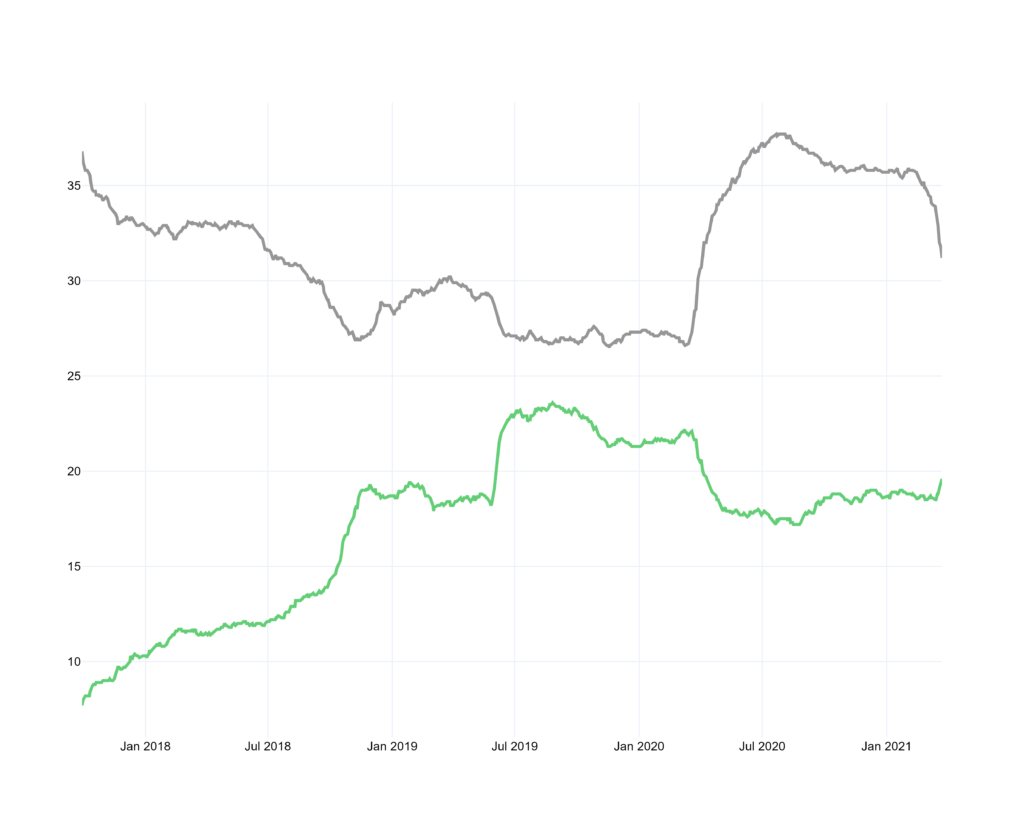

The tricky thing here though is, where will those 3-5% come from? Right now, the Green Party and the Christian Conservatives (CDU/CSU) mirror each other in popularity — if one loses support, the other party gains it.

Looking at the polling average of both parties for the 2021 election cycle, this becomes instantly clear. This of course is not a one-to-one relationship, though. Either party could pick off votes from the SPD or siphon votes off their respective political sides (CDU/CSU from the FDP and AFD, the Grüne from the SPD and the Linke).

Since this scenario becomes possible with about a 3% shift, it lies in the margin of error territory. It’s very possible — especially in a very volatile, unpredictable year — that this will occur.

Scenario III: The Greens join forces with the SPD and the FDP

These three parties currently have a combined voting share of 42.2%. They need at least 8%, more likely 9-11% more to form a government. The question here is similar to the one above: where will the votes come from? There really is only one plausible way: enough voters from the CDU/CSU have to switch over to the Green Party and the FDP.

It would be extraordinary for the Grüne to pick up that many votes by themselves. In February/March 2020, they reached their peak in my model’s projection. However, even at this peak, they still wouldn’t have had enough votes to form a governing coalition with the SPD and FDP.

The FDP tends to benefit from a weaker CDU/CSU as well and could gain votes. Nonetheless, the model has consistently projected them to win around 8 to 9%. This is most likely their ceiling in this election cycle.

The Green party would need to gain the majority of these 8 to 11 points and that would be a big shift, which makes this scenario not impossible, but the least likely out of the three.

We’re now entering what I’d categorize as highly unlikely territory with these last two scenarios.

Scenario IV: The Greens join forces with the SPD and the Linke

Just two election cycles ago, the three parties of the left had a razor-thin majority (which did not result in a coalition government). Today, the three parties on the left of Germany’s political spectrum are projected to win around 41.5%. The situation is quite similar to Scenario III with one big exception: it would be solely up to the Greens to make up these additional points since neither the Linke nor the SPD can be expected to pick up many points from the conservative parties.

Basically, Scenario IV is Scenario III but without the potential gains from the FDP.

Scenario V: The unwanted grand coalition

Both parties currently forming the governing coalition (referred to as the grand coalition) are projected to win 43.6% of the vote. This number is higher than scenarios III and IV — so why is this the unlikeliest scenario? The underlying fundamentals that would accompany a shift in the favor of the CDU/CSU and SPD make it so.

If they were to make up the 6-9% they need for a majority, they would not need each other anymore. If the conservatives become more popular, they could enter a coalition with the Greens or the FDP, or both. On the other hand, if the Social Democrats (SPD) gain in popularity, they could enter a coalition with more preferred partners — smaller ones. In this kind of coalition, they’d have a bigger say.

Additionally, three of the four Merkel governments were grand coalitions with the SPD. The Social Democrats are reported to be fed up with being the junior partner and only reluctantly entered a grand coalition after the last election in 2017 (they refused initially, but later gave in).

Another grand coalition between the CDU/CSU and the SPD almost seems impossible given all the reasons laid out above so this scenario has little chance of becoming reality.

What the future holds

The future doesn’t hold any game-changing events before the federal election in September. At least, none that can currently be anticipated.

Saxony-Anhalt will hold elections for the Landtag (regional parliament) in June. Current polls suggest the government in the state will remain unchanged. This would be in line with the regional elections in Baden-Würtemberg and Rhineland-Palatinate (both took place on March 13, 2021), which maintained the status quo. Note that Saxony-Anhalt is a smaller and less important state. Even if the ruling parties were to change there in June, it wouldn’t feature that prominently in the national discussion.

We are also still waiting on announcements from the Greens and the Christian Democrats regarding their candidate for chancellor and their party platform. The CDU/CSU did elect their new party leader, Armin Laschet, in January, which makes him the most likely candidate. The SPD has announced both their candidate and platform already. Olaf Scholz became their candidate in August 2020 and they presented their campaign platform in March of this year. None of these events had any noticeable effect on either party’s polling numbers or projections in the model.

In a regular election year (not that there really is such a thing), these are all the major events that could be anticipated. Germany is looking at a close election, which could end up being messy and result in long coalition negotiations. These would most likely be between a weakened (but still dominant) CDU/CSU, an underperforming Green Party, and a slightly overperforming FDP.

If 2020 taught us anything though, it’s that anything can happen…but 2020 also taught us that data and prediction models are important. And with that, there’s your raison d’ètre for this post (and this blog).

You can find the latest polling average and model predictions on the model page. I’ll post more state-of-the-race updates as we get closer to election day and will link to them here.